Note: This guest article is a contribution by a professional biologist who wishes to remain anonymous for professional reasons.

Background Information:

The Umatilla calls have caused much media sensation, with suspicions that they possibly could be sasquatch calls. Wildlife professionals and members of the public have also suggested that these calls were those of foxes, coyotes, or wolves. All four hypotheses were examined utilizing bioacoustic software Ishmael © (an open source program) and MATLAB.

Methods:

Calls were input into Ishmael © to obtain spectrogram and waveform characteristics, in order to visually compare calls with other possible culprits. Calls were compared against audio recordings of fox calls, fox cries (http://www.angelfire.com/ar2/thefoxden/), wolf howls and wolf pup howls, as well as a coyote howl. Calls were compared for spectrogram characteristics, as well as frequency characteristics, as determined in MATLAB software (Osprey analysis package).

First, the Umatilla calls were downloaded (http://www.oregonlive.com/pacific-northwest-news/index.ssf/2013/01/strange_sounds_coming_from_a_s.html) and input into Ishmael to obtain a spectrogram (below)

Some of the characteristics of the recordings made the calls particularly hard to analyze, namely distance from the animal being recorded, poor recording quality, and high amounts of background noise obscuring the calls (low signal-to-noise ratio).

Individual calls (seven in total) were extracted into Osprey for visual comparison of details and detailed analysis of characteristic frequencies:

Once the Umatilla calls were extracted, they were compared to a variety of animal sounds. Calls were compared in-depth with eight individual fox calls (from 2 separate recordings), as a fox appeared to be a likely culprit.

Initially, fox calls were input into Ishmael to determine frequency and call characteristics. The image below shows a high quality recording of a fox call in Osprey with visible harmonics.

The calls were scaled for visual comparison with Umatilla calls. To better determine this point, see below an Umatilla call superimposed over a randomly selected fox call. Note the general overlap of fundamental frequency and formant (first harmonic).

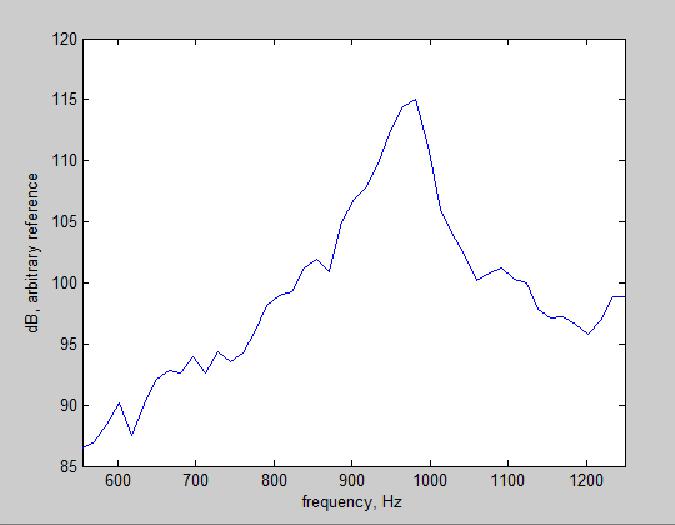

Next, the power spectrum (a comparison of frequency over dB power for a particular section of the call) was compared between the Umatilla call and the fox call super imposed above. Noise in the Umatilla call degraded the signal, but a clear correlation was visible upon comparison of both fundamental frequencies and fundamental frequencies plus first harmonic.

Fundamental frequency and first harmonic power spectra for fox (top) and Umatilla call (bottom) below:

Fundamental frequency spectra for fox (top) and Umatilla call (bottom) below:

The power spectra are very similar in form and peak signal, suggesting the calls are of the same general format and frequency.

To give additional statistical information, call characteristics (frequency low, frequency high, and peak overall frequency of both fundamental frequencies and first formant) were recorded and compared. Fox calls used were from two separate recordings, for a total of 8 calls. Click to download the Excel Spreadsheet for these values.

Next, in order to examine the possibility of other local wildlife, the calls were compared with an adult wolf howl, a wolf pup (not shown here), and an adult coyote howl. The fundamental frequencies of all these calls were not comparable to the Umatilla calls in a way that suggests these species were the culprit.

Below are shown the adult wolf and coyote calls. Note individual characteristics.

In general, wolf calls are of a frequency too low to be considered the culprit here. The fundamental frequency of a wolf is between 150-780Hz (Theberge and Falls 1967), well below the 1kHz fundamental frequency in the recordings. Wolves have up to 12 harmonics, spaced by approximately 0.5kHz. Although the Umatilla calls were weak, they appeared to only have one strong harmonic. The wolf call in the spectrogram above has a fundamental frequency of 0.5kHz.

Wolf pups were also considered, but the characteristics of the call did not appear to match the call of interest upon general inspection. Additionally, pups are usually born between March and June annually, and begin howling at 2 weeks of age. It is unlikely that these are pup calls, simply due to timing.

Coyotes were also considered as a possible culprit, to round out the analysis. However, upon importing a coyote call, it became apparent that the call characteristics, as well as the fundamental frequency do not match that of the recording in question:

Note that the fundamental frequency is approximately 0.75kHz, with the first format or harmonic slightly above 1.5kHz. This is similar, but doesn’t have the same sweeping motion as the mystery calls.

Therefore, coyotes can also be ruled out as the likely species.

Results

Due to call similarity in frequency, characteristics, and sound, it is very likely that these mystery animals are foxes. The Excel statistics demonstrate very similar frequencies between the Umatilla calls and fox calls. Due to a relatively small sample size, however, it is difficult to accurately determine p-values for these.

The possibility of a calling sasquatch can of course be considered, but one must keep in mind that vocal tract length is very much correlated with body size, and with increased vocal tract length comes lower frequency communication. Sasquatches have even been suspected of utilizing infrasound (sound below the 20Hz range of human hearing) and an animal of that suspected size would almost certainly have a lower frequency of vocalization than humans, which range from 300Hz with an upper limit of 3kHz. The recordings here suggest that the animal in question is quite small, being that it is completely within the kHz range of communication. So bigfoot? Probably not. Juvenile? Maybe, but there is nothing to compare this to. A good next step would be to compare the calls to suspected bigfoot calls. However, that was precluded in this ‘quick and dirty’ analysis because of the high frequency of the recorded Umatilla calls.

Additional Sources:

Theberge, John B., and J. Bruce Falls. “Howling as a means of communication in timber wolves.” American Zoologist 7.2 (1967): 331-338.